In search of bad vibes

A mood of boiling discontentment in Britain is the subject of daily news - but where is the evidence that it even exists?

Britain is “fraying around the edges,” at “boiling point” and on the brink of ‘civil disobedience on a vast scale,’ with the north of England set to “go up in flames” if the anger and resentment continue to simmer. These, at least, were claims made over the last couple of weeks by prominent politicians, among them the Prime Minister.

A day doesn’t go by at the moment without comment pieces in the national press or remarks by politicians to the same effect. The British people are discontented, they claim - exhausted, frustrated, angry, and at their wits end - and so much so that the country is a powder keg that just needs one small spark.

This exact image was invoked by the authors of the report Shattered Britain, published earlier this month, which used new polling data to paint a gloomy picture of a people broken by permacrisis. The authors of the report, thinktank More in Common, found from bespoke polling that three quarters of people thought the government didn’t have things under control and half suspected the cost-of-living crisis would never end.

Summer does bring out disobedience, and not just in the UK - but the way commentators are talking about Britain’s volatile mood in the press feels more existential than usual and more urgent. The only thing is, when you look at the hard evidence of how people are feeling and try to pin down what exactly is behind the crisis of mood, there’s barely anything there at all.

How are people really feeling?

Looking at reputable data on people’s wellbeing and mood in the UK, the overall picture is neither extremely positive or negative - it’s somewhere on the slightly warmer end of beige.

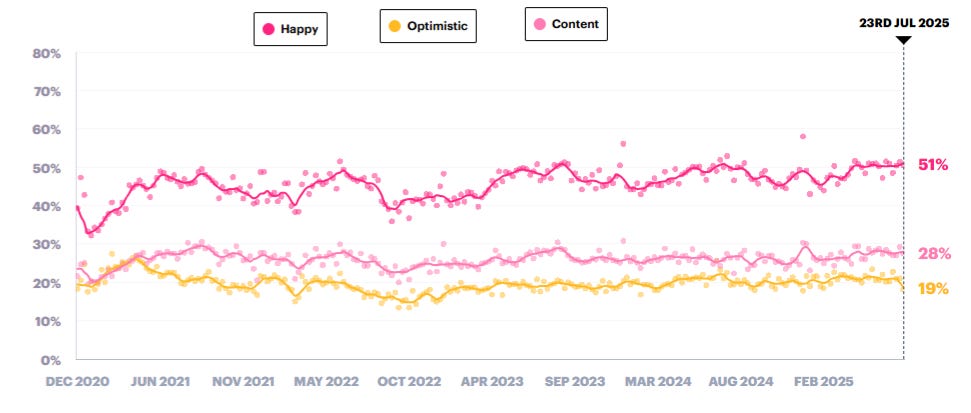

Take this YouGov tracker which asks people, ‘Broadly speaking, which of the following best describe your mood and/or how you have felt in the past week [Please select all that apply]’. ‘Happy’ tends to be the most common mood reported. Happier and sadder moods have been quite consistent over the past five years.

The lines are very steady and there are no down- or up-turns in recent weeks that would suggest mass civil unrest is on the cards. Another poll shows life satisfaction tracking at a pretty solid 6 out of 10 the whole time it’s been measured. But this YouGov data only covers a five-year period - maybe what’s being picked up here is a more persistent and dangerous low mood.

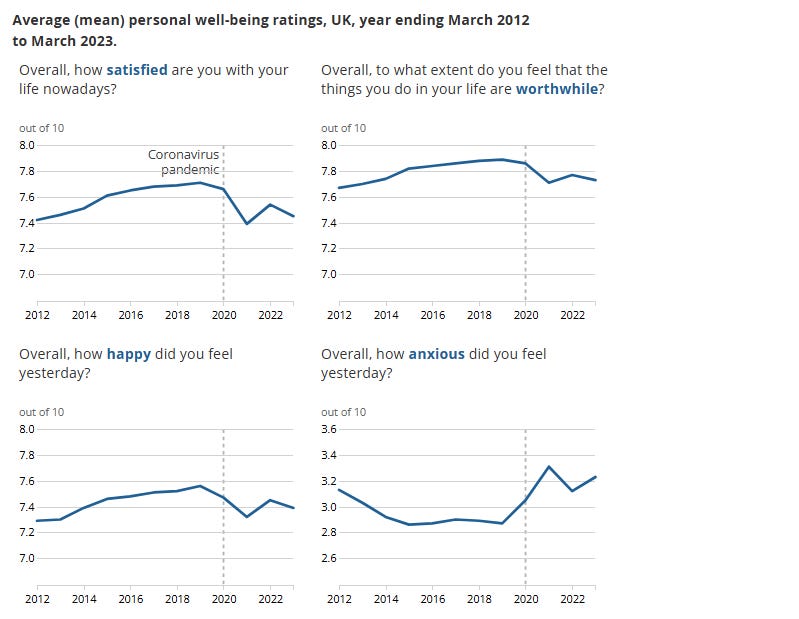

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has an answer to that, in its annual data on people’s self-reported personal wellbeing. Although the most recent data here is less timely than YouGov’s tracker, we can see broad patterns. The Covid pandemic clearly did a number on our wellbeing - increasing anxiety in particular - but reported life satisfaction was actually still better in 2022/23, at a point when the cost-of-living crisis was worse than now, than it had been in 2011/12.

If we want to look over an even longer time period, we can use data from longer-running international surveys. Below, data from the Integrated Values Survey (IVS) shows that UK happiness was a bit lower in 2022 than in 1985 but still remarkably high and more stable than in other comparable countries.

As a sidenote: it’s also interesting to see what a different picture we get depending on the specific question. The IVS suggests that over 90% of Brits are happy overall but the YouGov survey shows that typically around 50% of them consider happiness their dominant mood in a given week.

Happy people raging against the system?

You might say that people’s self-reported personal wellbeing is a separate issue to how they feel about the state of the country, and that happy people can still boil with fury when they think about their leaders.

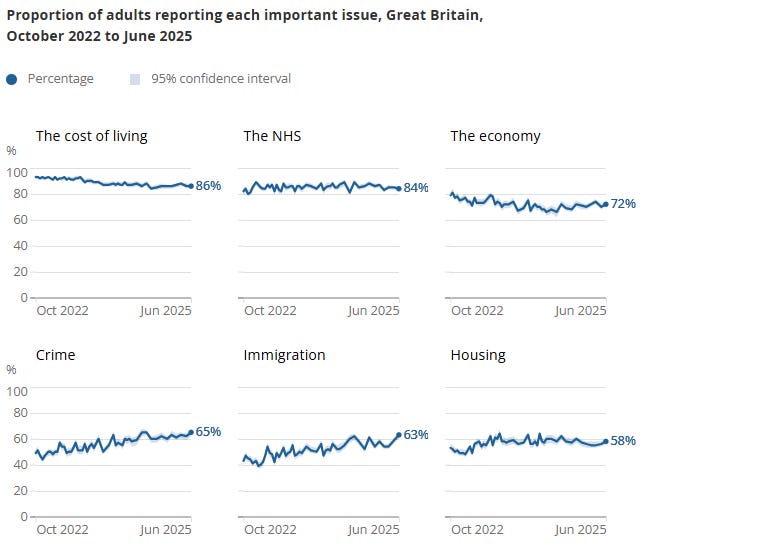

But the data on what people think about public affairs and the state of the system also doesn’t show any particular red flags. The ONS tracks what people consider important issues, and while those show some slow changes over time, nothing stands out over the past year or so.

On the economy, the GfK Consumer Confidence Survey - a barometer of how at ease people feel about spending significant sums of money - doesn’t look great but is still much better than it was two years ago. Despite a stagnating economy, consumer confidence has bounced back from the pandemic better than it did from the 2008 financial crisis.

People’s trust in politicians is low and trust in some institutions has also gradually been slipping downwards in the UK, following a trend across developed countries. Polling company Ipsos recorded its lowest ever rating of trust in politicians in 2023, with just 9% of Brits saying they generally trusted them - but this had improved again in 2024, albeit to a measly 15%.

Of course, the polling in ‘Shattered Britain’, which suggested a dangerously pessimistic mood, can’t be discounted. But this was a one-off survey, and without context as to how people would have answered these questions two or ten years ago, we really can’t point to it and warn of imminent social collapse. Another recent thinktank report, the accusingly-titled ‘The State of Us’, found that only 9% of people reported a lack of social cohesion in their area.

Belief in a vibe doesn’t make it real

In 2022, economic commentator Kayla Scanlon coined the term ‘vibecession’ to describe what was happening in the American mind. While the economy was recovering well post-pandemic, consumers still felt insecure and pessimistic about the country’s finances and their own. This happens because even when, for example, inflation levels falls after a period of increase, people are still unhappy with having to spend more than in the recent past to consumer the same amount. What is happening in the UK now also looks like a case of bad vibes.

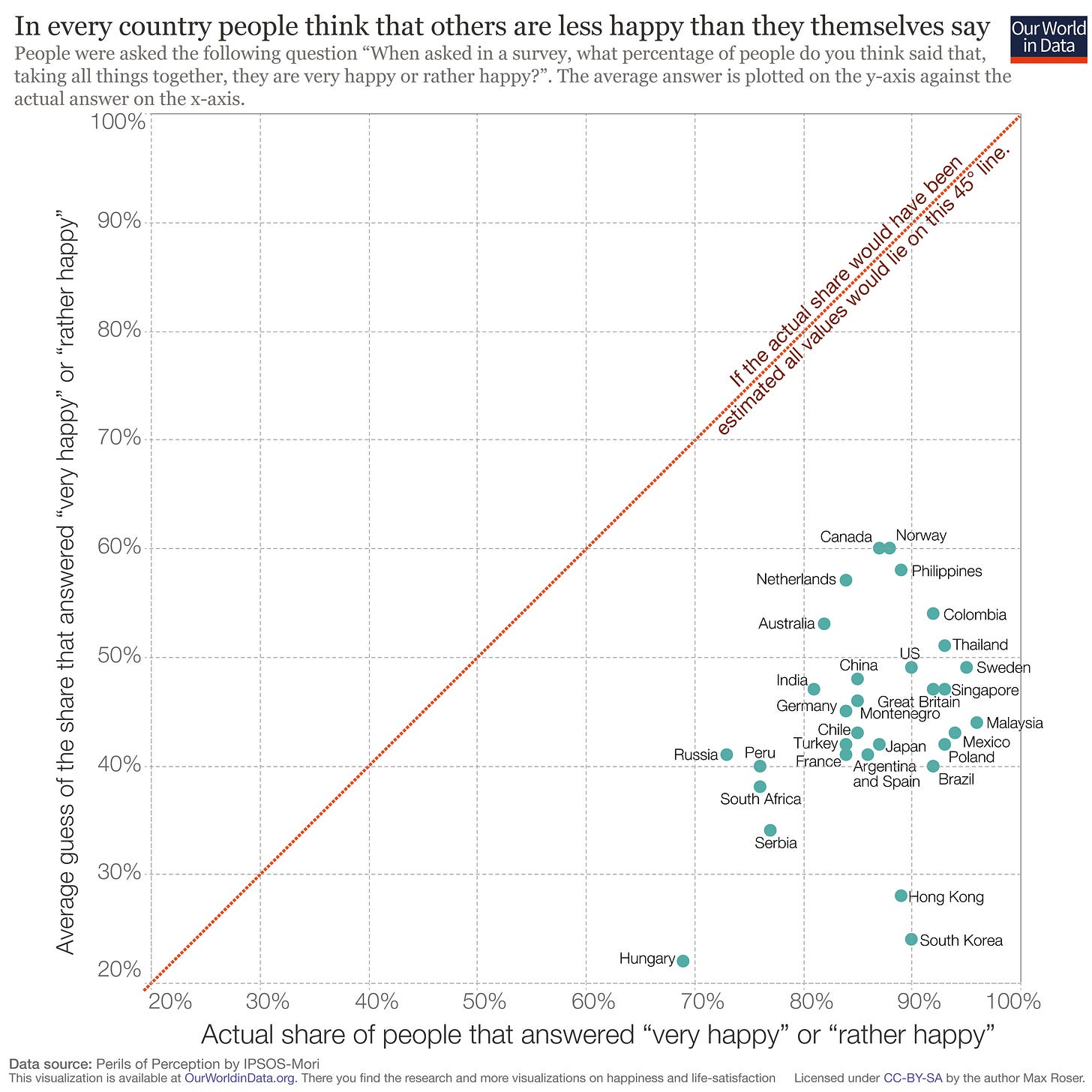

It’s well-established that people tend to have a more pessimistic view of situations the further away they are from their immediate surroundings. This chart from Our World in Data shows a stark example of how, in every country in the world, people gave a much lower rating to their perception of other people’s happiness than the actual share (and indeed their own happiness).

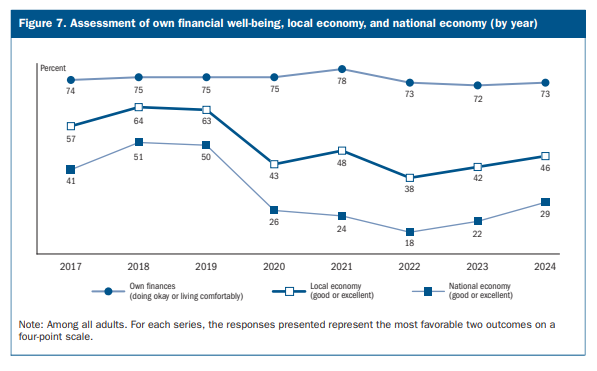

When it comes to the economy, people have also been proven to give a much worse rating to the performance of the national and local finances than their own household situation. Take this survey, from the US Federal Reserve, which showed that, in 2024, 73% of Americans rated their own financial situation while only 29% felt the same about the national economy.

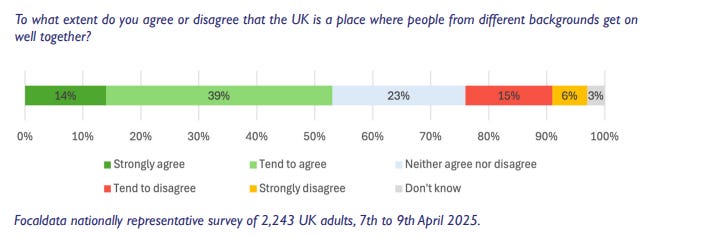

It’s a phenomenon that Ipsos has referred to as the ‘perils of perception.’ Within this pattern, people are also more likely to over-estimate the size of minority groups and perceive society to be more culturally fragmented than it is. In 2024, people in the UK estimated, on average, that 21% of the population was Muslim, while the real figure was 6%.

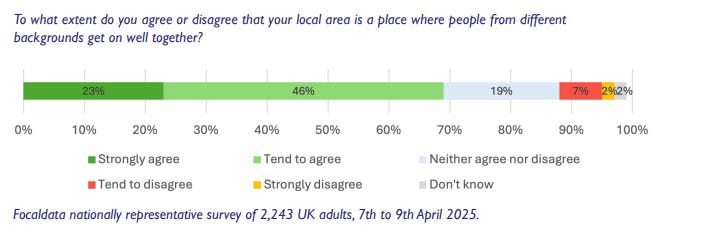

We can see the perils of perception at work in the ‘State of Us’ report, where people’s perception of community cohesion across the UK was much worse overall than the ratings people actually gave about their communities.

The only really concerning statistics that are feeding into the idea that the UK is at ‘boiling point’ are about people’s reflections of what the general state of the country is like, rather than their own lives. And people’s view of distant or national-level phenomena tends to be pessimistic and wide of the reality. Frankly, there is little value to this data except to point out the curious gulf between reality and, well, vibes.

But there is something going on

I’ve done this analysis to investigate whether the national-level situation in the UK is as dire as many people claim. But of course, averages and national-level statistics present an impression in which extremes of opinion or experience are smoothed away. The experience of living in the UK in 2025 is certainly not universal. There are segments of the population with specific grievances and burying those away by pointing to overall statistics that show ‘everything is fine’ is not good politics (nor the intention of this piece).

We can probably tell best where the strength of feeling is - and where the warning signs are for politicians - by the dramatic swings in people’s stated voting intentions in recent years. As of this month, Reform stood on 27% of the prospective vote, well above both Labour and the Conservatives. But 27% is not even close to a majority, is it, in terms of the proportion of people tempted towards what is largely a single-issue protest vote?

It is a problem that trust in politicians is so low - this is bound to make people feel irritated and unheard at times, even if goings on in Westminster don’t define their daily lives or overall mood. But this is not just a problem for the UK - trust ratings in the USA have been on the floor for decades, no matter who the President is. It has also got worse in a lot of European countries, and populist parties have become an answer for many voters.

Some people in the UK are very angry. Most people are not. Mass civil disobedience would be very unexpected given what the reliable data appear to be telling us. Yet dip into any mainstream, social, or fringe form of media and you’re likely to find the situation represented as it is in this Times cartoon below. We’re convinced now that something massive and brutal is about to erupt.

Without wanting to sound patronising, what’s missing is some perspective. People are clearly able to apply perspective when reporting that their lives are ‘happy’ overall even if they didn’t feel that way for the majority of the past week. The media, by design, does not do the same. And let’s face it we all revel in a bad vibe, providing it’s not in our own immediate lives.